Cillian Murphy hates spoilers. The clue is in the word, says the 38-year-old actor: to spoil something is to ruin it, and why would you want to ruin someone’s entertainment? So we are at a slight loss, he and I, to describe Ballyturk, the play by his old friend and collaborator Enda Walsh, that has lured the star of Peaky Blinders, Batman Begins and 28 Days Later back to the stage. Not least because Ballyturk defies easy description.

“Well, I’ll tell you what, Nick, it’s not really a what’s-it-about play,” Murphy says, the accent of his native Cork thicker in real life. “The themes it deals with are friendship and loss and I think creative life. It is very kinetic, very visceral theatre, but also very precise. He likes to make actors work — I always say you get tremendously fit doing an Enda Walsh show.”

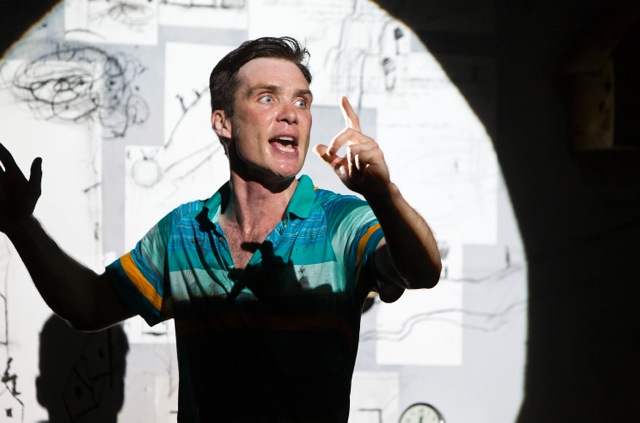

Indeed. Without giving too much away, I can tell you that Ballyturk features Murphy and Mikel Murfi in a huge room, performing manic comic rituals that seem designed to stave off existential dread, including the summoning or impersonation of various colourful characters from the titular Irish town. There’s a lot of mid-Eighties pop music and physical comedy, and towards the end Stephen Rea ominously turns up. There are echoes of Becket’s Waiting for Godot, just as there were echoes of Krapp’s Last Tape in Walsh’s Misterman, the monologue about a religious man recalling past encounters, that Murphy triumphantly bought from Ireland to the National in 2012.

This is the third collaboration between writer and star: in 1996 Murphy, who comes from a family of educators and was then an aspiring rock musician and law dropout, made his stage debut in Walsh’s tale of two Cork tearaways, Disco Pigs, which became a runaway hit. “I was very lucky to have the standard set so high for me,” says Murphy. “We didn’t know at that time he was a significant writer. He was just a young writer with energy and attitude. And great hair. So I was spoilt. It was a break for me. I just love his sense of humour, the way he smashes comedy up against tragedy. His plays could never work on television or film, they are so purely theatrical. And he is a beautiful wordsmith. For an actor to be given these beautiful speeches is a great gift.”

Rock dreams were forgotten and for the next six years Murphy acted mostly on stage, until fame intervened: Danny Boyle cast him as the lead in his zombie film 28 Days Later, bringing out the steel edge to his delicate beauty, the riveting cornflower eyes.

After small parts in Girl with a Pearl Earring and Cold Mountain he auditioned, without much hope, for the lead role in Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins, and was rewarded instead with the scene-stealing part of the Scarecrow. Then came the thriller Red Eye, the Wind that Shakes the Barley for Ken Loach, a stunning turn as a transsexual in Breakfast on Pluto for Neil Jordan, Boyle’s Sunshine and The Dark Knight and Inception for Nolan.

“Suddenly I hadn’t done a play in six years and I said it’s ridiculous that I haven’t collaborated with my close friend and brilliant writer Enda, so we went and did Misterman,” he says. “I realised how much I had missed [theatre]. Getting to act with your whole body is so liberating for me. I am not really known for my comedy, and Enda’s shows allow me to release the funny bones a bit. If your ambition is to improve as an actor, as mine is, theatre is the form to do it. I love that contact between an audience and a performer — we are all sitting in a darkened room and the potential for things to go wrong is so extraordinarily high. So the goodwill between performer and audience is paramount to the thing’s success. And when live theatre does succeed, there’s nothing like it.”

Murphy is fortunate to be working at a time when theatre in both London and Ireland is strong (Ballyturk, like Misterman, premiered in Galway), and when there is less snobbery and greater fluidity for actors to move between media. He has shrugged off implied criticism for appearing in blockbusters. “You follow the word on the page and if the word on the page is strong, the budget is irrelevant,” he says.

Thus he was happy to act on the shoestring-financed Broken for Rufus Norris, the National’s incoming artistic director, and is happy to be in the megabudget In the Heart of the Sea next year. The film is based on the 1820s account of a Nantucket whaling ship “stoved in by this angry white whale, and how the crew survive, or not” that inspired Moby Dick. “It’s Ron Howard directing and he is such a tremendous storyteller,” adds Murphy. “What I loved about it was that it was such a proper old-fashioned movie: men, sea, the elements and a whale. There’s no chance of a spin-off, no aliens. I think people will really respond to it.”

He thinks that mid-budget, intelligent movie making has collapsed, but that the writers moved to TV, dragging the rest of the industry with them, hence the burgeoning nature of small-screen drama. He has spent most of this year filming series two of Peaky Blinders, Steven Knight’s gripping tale of inter-war Birmingham gangsters, in which he plays ruthless kingpin Tommy Shelby. Again, there are no spoilers.

“It’s common knowledge that the story goes south…” he laughs and stops himself. “Not ‘south’ in that sense, let me rephrase that — that Tommy and the gang go to London, and that’s when they encounter Tom Hardy and other London gangs. The story is expanding. I’ve worked with Tom a couple of times and I just love what he can do: he’s very bold in his choices, always pushing it. It’s a brilliant creation Steve Knight wrote for him, and there should be some very exciting scenes in it.”

He hasn’t worked out yet whether the National’s schedule will enable him to see his Peaky Blinders co-star Helen McCrory in Medea, which is playing in the Olivier while Ballyturk is in the Lyttelton. He says he loves London’s restaurants, galleries and theatres but this very private star is equally happy having a quiet life at home in a villagey part of north-west London with his wife, artist Yvonne McGuinness, and their sons Malachy, nine, and Aran, seven, not far from Walsh and his family.

“There’s a lot of people like us there — what my friend called ‘fathers in media’,” he laughs. He and Walsh both rented there when they first moved from Ireland, then basically stayed. “That happens with London: you stay in the place where you land because it’s so vast. I have friends in south London and never see them: it might as well be another country. The times I do go, I say wow it’s beautiful. But it takes so feckin’ long to get there.” Maybe this new stint on the South Bank will encourage him.

Written by Nick Curtis in The Evening Standard on 01.08.14